Apéry's theorem

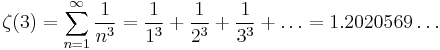

In mathematics, Apéry's theorem is a result in number theory that states the Apéry's constant ζ(3) is irrational. That is, the number

cannot be written as a fraction p/q with p and q being integers.

Contents |

History

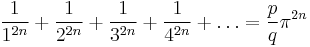

Euler proved in the eighteenth century that if n is a positive integer then we have

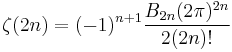

for some rational number p/q. Specifically, writing the infinite series on the left as ζ(2n) he showed

where the Bn are the rational Bernoulli numbers. Once it was proved that πn is always irrational this showed that ζ(2n) is irrational for all positive integers n.

No such representation in terms of π is known for the so-called odd zeta constants, the values ζ(2n+1) for positive integers n. It has been conjectured that the ratios of these quantities

are transcendental for every integer n ≥ 1.[1]

Because of this, no proof could be found to show that the odd zeta constants were irrational, even though they were—and still are—all believed to be transcendental. However, in June 1978 Roger Apéry gave a talk entitled "Sur l'irrationalité de ζ(3)." During the course of the talk he outlined proofs that ζ(3) and ζ(2) were irrational, the latter using methods simplified from those used to tackle the former rather than relying on the expression in terms of π. Due to the wholly unexpected nature of the result and Apéry's blasé and very sketchy approach to the subject many of the mathematicians in the audience dismissed the proof as flawed. Three of the audience members suspected Apéry was onto something, though, and set out to confirm his proof.

Two months later these three—Henri Cohen, Hendrik Lenstra, and Alfred van der Poorten—finished their work, and on August 18 Cohen delivered a lecture giving full details of Apéry's proof. Following the talk Apéry himself took to the podium to explain the source of some of his ideas.[2]

Apéry's proof

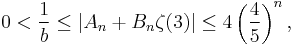

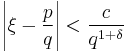

Apéry's original proof[3][4] was based on the well known irrationality criterion from Dirichlet, which states that a number ξ is irrational if there are infinitely many coprime integers p and q such that

for some fixed c,δ>0.

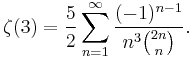

The starting point for Apéry was the series representation of ζ(3) as

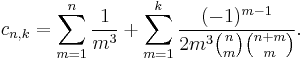

Roughly speaking, Apéry then defined a sequence cn,k which converges to ζ(3) about as fast as the above series, specifically

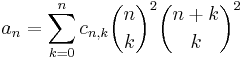

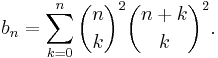

He then defined two more sequences an and bn that, roughly, have the quotient cn,k. These sequences were

and

The sequence an/bn converges to ζ(3) fast enough to apply the criterion, but unfortunately an is not an integer after n=2. Nevertheless, Apéry showed that even after multiplying an and bn by a suitable integer to cure this problem the convergence was still fast enough to guarantee irrationality.

Later proofs

Within a year of Apéry's result an alternative proof was found by Frits Beukers,[5] who replaced Apéry's series with integrals involving the shifted Legendre polynomials  . Using a representation that would later be generalized to Hadjicostas's formula, Beukers showed that

. Using a representation that would later be generalized to Hadjicostas's formula, Beukers showed that

for some integers An and Bn (sequences A171484 and A171485). Using partial integration and the assumption that ζ(3) was rational and equal to a/b, Beukers eventually derived the inequality

which is a contradiction since the right-most expression tends to zero and so must eventually fall below 1/b.

A more recent proof by Wadim Zudilin[6] is more reminiscent of Apéry's original proof, and also has similarities to a fourth proof by Yuri Nesterenko.[7] These later proofs again derive a contradiction from the assumption that ζ(3) is rational by constructing sequences that tend to zero but are bounded below by some positive constant. They are somewhat less transparent than the earlier proofs, relying as they do on hypergeometric series.

Higher zeta constants

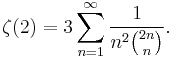

Apéry and Beukers could simplify their proofs to work on ζ(2) as well thanks to the series representation

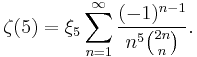

Due to the success of Apéry's method a search was undertaken for a number ξ5 with the property that

If such a ξ5 were found then the methods used to prove Apéry's theorem would be expected to work on a proof that ζ(5) is irrational. Unfortunately, extensive computer searching[8] has failed to find such a constant, and in fact it is now known that if ξ5 exists and if it is an algebraic number of degree at most 25, then the coefficients in its minimal polynomial must be enormous, at least 10383, so extending Apéry's proof to work on the higher odd zeta constants doesn't seem likely to work.

Despite this, many mathematicians working in this area expect a breakthrough sometime soon.[9] Indeed, recent work by Wadim Zudilin and Tanguy Rivoal has shown that infinitely many of the numbers ζ(2n+1) must be irrational,[10] and even that at least one of the numbers ζ(5), ζ(7), ζ(9), and ζ(11) must be irrational.[11] Their work uses linear forms in values of the zeta function and estimates upon them to bound the dimension of a vector space spanned by values of the zeta function at odd integers. Hopes that Zudilin could cut his list further to just one number did not materialise, but work on this problem is still an active area of research. Higher zeta constants have application to physics: they describe correlation functions in quantum spin chains, see for example[12].

References

- ^ Kohnen, Winfried (1989). "Transcendence conjectures about periods of modular forms and rational structures on spaces of modular forms". Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. Math. Sci. 99 (3): 231–233. doi:10.1007/BF02864395.

- ^ A. van der Poorten (1979). "A proof that Euler missed...". The Mathematical Intelligencer 1 (4): 195–203. doi:10.1007/BF03028234. http://www.maths.mq.edu.au/~alf/45.pdf.

- ^ Apéry, R. (1979). "Irrationalité de ζ(2) et ζ(3)". Astérisque 61: 11–13.

- ^ Apéry, R. (1981), "Interpolation de fractions continues et irrationalité de certaines constantes", Bulletin de la section des sciences du C.T.H.S III, pp. 37–53

- ^ F. Beukers (1979). "A note on the irrationality of ζ(2) and ζ(3)". Bull. London Math. Soc. 11 (3): 268–272. doi:10.1112/blms/11.3.268.

- ^ W. Zudilin (2002), An Elementary Proof of Apéry's Theorem.

- ^ Ю. В. Нестеренко (1996). "Некоторые замечания о ζ(3)" (in Russian). Матем. Заметки 59 (6): 865–880. http://mi.mathnet.ru/mz1785. English translation: Yu. V. Nesterenko (1996). "A Few Remarks on ζ(3)". Math. Notes 59 (6): 625–636. doi:10.1007/BF02307212.

- ^ D. H. Bailey, J. Borwein, N. Calkin, R. Girgensohn, R. Luke, and V. Moll, Experimental Mathematics in Action, 2007.

- ^ Jorn Steuding (2005). Diophantine Analysis (Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications). Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1-58488-482-8.

- ^ Rivoal, T. (2000). "La fonction zeta de Riemann prend une infinité de valeurs irrationnelles aux entiers impairs". Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. Paris Sér. I Math. 331: 267–270. arXiv:math/0008051. doi:10.1016/S0764-4442(00)01624-4.

- ^ W. Zudilin (2001). "One of the numbers ζ(5), ζ(7), ζ(9), ζ(11) is irrational". Russ. Math. Surv. 56 (4): 774–776. doi:10.1070/RM2001v056n04ABEH000427.

- ^ H. E. Boos, V. E. Korepin, Y. Nishiyama, M. Shiroishi (2002). "Quantum Correlations and Number Theory". Journal reference: Journal of Physics A 35: :4443–4452.

![\int_{0}^{1}\int_{0}^{1}\frac{-\log(xy)}{1-xy}\tilde{P_{n}}(x)\tilde{P_{n}}(y)dxdy=\frac{A_{n}%2BB_{n}\zeta(3)}{\operatorname{lcm}\left[1,\ldots,n\right]^{3}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/514d38b3cd99ea8893038691aaafa59c.png)